PID Control #

Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) Control is an extremely popular method for controlling various actuators on hobbyist and industrial robots alike. Its popularity is due both to its simplicity and effectiveness for a wide range of systems. As such, it is an important stepping stone to more sophisticated techniques.

Basics #

Before we dive into the mechanics of PID, it is useful to define some terminology. Every control problem arises from a real world mechanism or system with inputs and outputs. These systems are often referred to as plants. While a particular system may have multiple inputs and outputs, we will restrict our attention to single-input, single-output (SISO) plants. In this context, the objective of PID control is to adjust the input variable to yield the desired output (often called the setpoint). PID control is a form of feedback control which uses measurements of the output to determine the input (we’ll see the complementary technique of feedforward control in the next section). This is accomplished by minimizing error—the difference between the current output and the setpoint.

To see this in action, consider the problem of controlling the position of a linear slide actuated by a spool attached to a motor. In this example, the linear slide system is the plant, the single input is the motor voltage, and the single output is the linear slide position.

As a matter of convention, the variables should be defined so that an increase in the input variable results in an increase in the output variable.

As the acronym suggests, the output of a PID controller is composed of three distinct components. The proportional term produces a control input in direct proportion to the error signal. That is, if the error doubles, the control input will also double. Mathematically, this is expressed by the equation \( u = k_p \cdot e \) where \( u \) is the control input, \( k_p \) is the proportional gain, and \( e = x_{setpoint} - x \) is the error. The proportional gain is a tunable parameter that determines the aggressiveness of the control action. More on tuning at the end of this page.

While purely proportional (P) control is sometimes sufficient, it is not capable of handling every plant. To supplement it, one can use integral (I) control, derivative (D) control, or a combination of both. The integral term maintains a sum of the past errors which allows compounded small errors to accumulate into bigger errors. The derivative term measures the change in error to mitigate rapid fluctuations in the control input. To compute the total response, simply add the individual ones together: \( u = k_p \cdot e + k_i \int e \, dt + k_d \frac{de}{dt} \) .

With Road Runner, all of this is conveniently packaged in PIDFController (yes, there is indeed an F for feedforward—more about that in the next section).

// specify coefficients/gains

PIDCoefficients coeffs = new PIDCoefficients(kP, kI, kD);

// create the controller

PIDFController controller = new PIDFController(coeffs);

// specify the setpoint

controller.setTargetPosition(setpoint);

// in each iteration of the control loop

// measure the position or output variable

// apply the correction to the input variable

double correction = controller.update(measuredPosition);

// specify coefficients/gains

val coeffs = PIDCoefficients(kP, kI, kD);

// create the controller

val controller = PIDFController(coeffs);

// specify the setpoint

controller.targetPosition = setpoint;

// in each iteration of the control loop

// measure the position or output variable

// apply the correction to the input variable

val correction = controller.update(measuredPosition)

For some situations, the input variable wraps around (e.g., IMU heading). To prevent discontinuities in the error computations, use PIDFController.setInputBounds():

Tuning #

The real art of PID control is tuning the gains. This is traditionally done manually using a graph of the error over time or observing the plant’s behavior directly. Typically, one starts with a pure P loop. With a high enough gain, the output should oscillate around the setpoint. If the controller is unable to reach the setpoint over a long period of time (this is called steady-state error), it may help to add more integral action. This is often the case with static friction or significant inertia relative to the actuator force. Once the oscillations are centered around the setpoint, increasing the derivative gain can dampen the oscillations while still reaching the setpoint in the same amount of time.

Be careful when adding integral action to your controller. Without proper countermeasures, the response can easily become unstable with violent oscillations of increasing amplitude. This problem is often referred to as integral windup and can be mitigated by one or more of the approaches below:

- Capping the integral sum

- Decaying the integral sum over time

- Restricting integral action to a certain band around the setpoint

However, as we will see, a better solution is to determine the cause of the steady-state error and to integrate that knowledge into the controller with additional feedforward terms.

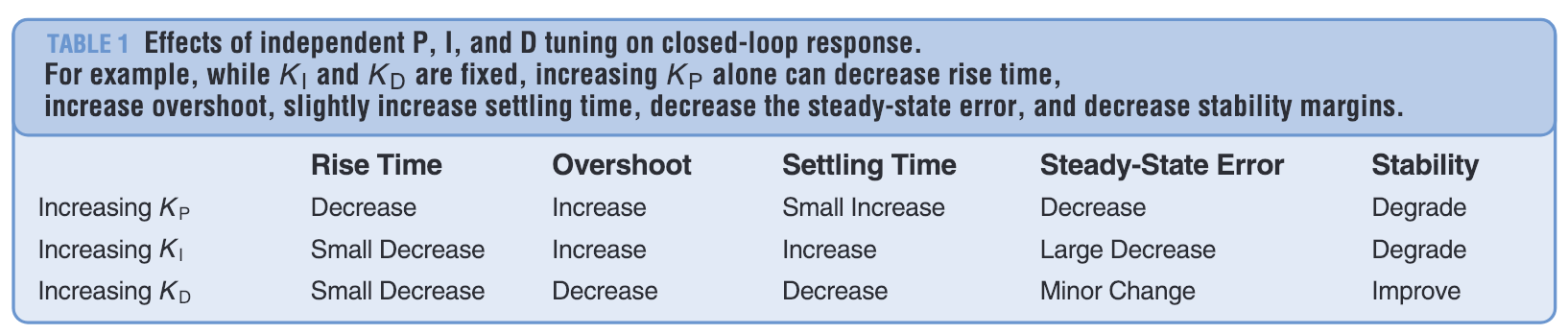

Here’s a chart summarizing the effects of each gain on the response:

If you want a semi-automated approach to tuning, check out the Ziegler-Nichols method.